By Emily R. Winslow, MD, FACS

Pancreatic cysts are being detected with increasing frequency with a prevalence now estimated to be up to 13% of the population when MR imaging is used. On routine imaging studies done for abdominal pain or other complaints referable to the abdomen, it is not uncommon for a clinician to confront the incidental finding of a pancreatic cyst. Because pancreatic cysts can range from benign inflammatory lesions to frankly malignant cystic masses, it is essential for clinicians to have a working knowledge of these lesions.

ETIOLOGY OF PANCREATIC CYSTS

Pancreatic cysts can be classified as either of non-epithelial or epithelial origin, and within each of those categories as non-neoplastic or neoplastic.

Non-Epithelial: Perhaps most familiar are the non-epithelial non-neoplastic cysts, which include both pseudocysts and parasitic cysts. Non-epithelial neoplastic cysts include lymphangiomas (benign) and sarcomas with cystic degeneration (malignant).

Epithelial: The most familiar non-neoplastic cysts of epithelial origin include lymphoepithelial cysts, periampullary duodenal wall cysts, retention cysts and congenital cysts. The vast majority of pancreatic cysts fall into the category of neoplastic epithelial cysts. This group can be subdivided into those that are benign, pre-malignant and malignant:

- Benign cysts of epithelial origin include most importantly serous cystadenomas, but also include less common conditions such as dermoid cysts and cystic hamartomas.

- Pre-malignant cysts of epithelial origin include the two most challenging conditions — mucinous cystic neoplasm (MCN) and intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN).

- Malignant epithelial cysts include invasive carcinomas that arise from either MCN or IPMN, cystic ductal adenocarcinomas, cystic neuroendocrine tumors, and solid pseudopapillary tumors.

DESCRIPTION OF IMPORTANT PANCREATIC CYST TYPES

Serous Cystadenoma (SCA): These cystic lesions are glycogen rich lesions that typically have the appearance of multiple small (sub-centimeter) cysts clustered together with thick fibrous walls and septations in a “honeycomb” type pattern (i.e. the microcystic variant of SCA). However, about 10% of SCAs have a macrocystic appearance and can more easily be confused radiographically with MCN and IPMN. The fluid within them is serous and they may arise in any part of the pancreas. Although there are reports of serous cystadenocarcinomas, these are quite rare with only about 30 case reports in the worldwide literature.

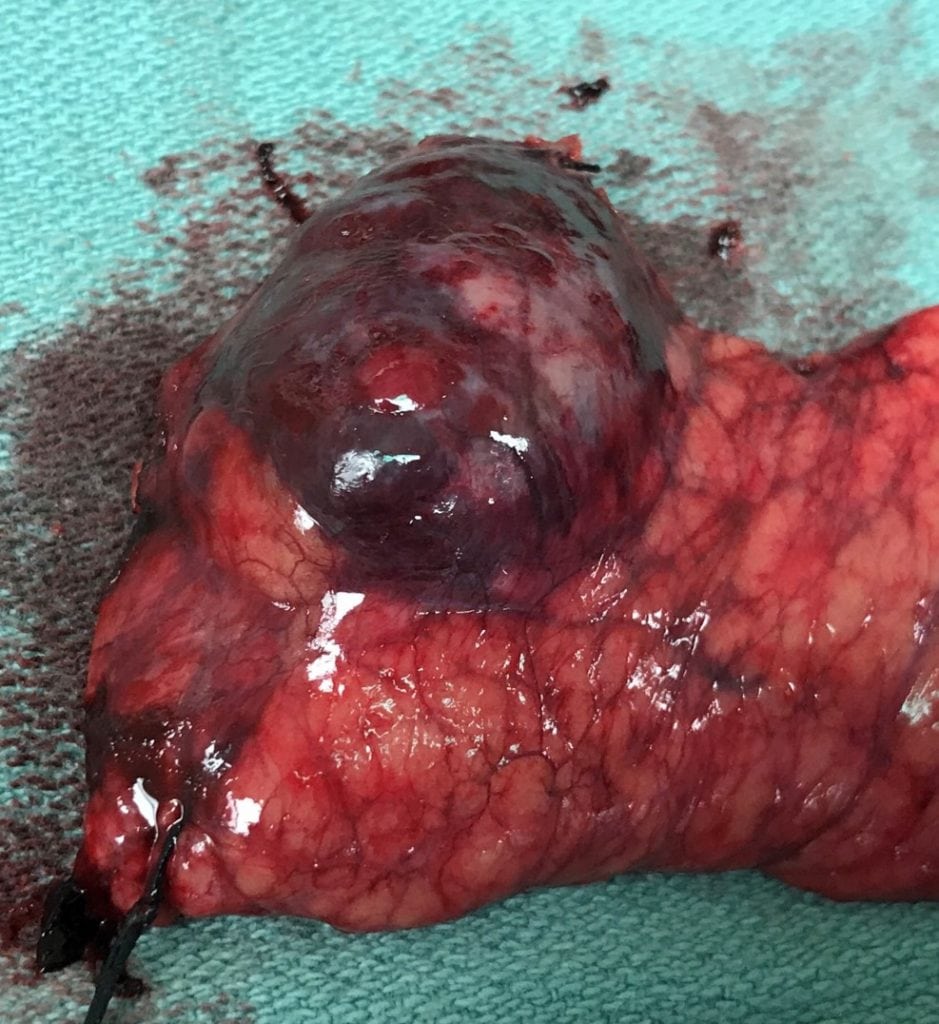

Mucinous Cystic Neoplasm (MCN): These cystic lesions are usually solitary cysts and are filled with mucin. They occur most commonly in the tail of the pancreas and are almost exclusively (>98%) found in women. Radiographically, they often have thick walls with scattered calcifications. They harbor a risk of in-situ or invasive malignancy that is estimated to be on the order of about 30%.

Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasms (IPMN): IPMNs come in two major types — those that arise from the main pancreatic duct and those that arise from its side branches.

- Main-duct IPMN is characterized by a dilated pancreatic duct (>5 mm) that is ectactic and mucin-filled (in the absence of pancreatic duct obstruction). This often involves the entire gland but can be segmental as well. The risk of high-grade dysplasia, in-situ or invasive malignancy is on the order of 60-70%.

- Branch-duct IPMN is a much more innocuous process of the pancreas that does not involve the main duct but instead is characterized by cysts within the parenchyma that come from the smaller ductules of the pancreatic exocrine drainage system. These by definition directly connect to either a side branch or the main duct, although the connection is not always seen by axial imaging. These are often multiple and often are scattered throughout the gland. Although they have malignant potential, the risk is low and dependent on specific cyst features.

HOW TO EVALUATE PANCREATIC CYSTIC LESIONS

In order to determine the necessary workup for a pancreatic cyst, the patient must first be thoroughly evaluated clinically. Essential clinical features that should be considered in the evaluation of patients with pancreatic cysts include the following: current symptoms thought to be referable to the pancreas, a prior history of pancreatitis, a family or personal history of pancreas or other related cancers or syndromes (e.g. multiple endocrine neoplasia). Medical comorbidities which place patients at a prohibitively high operative risk should be carefully evaluated in order to determine if pancreatic resection would be prudent. Older abdominal imaging is very helpful to obtain as well if available as it helps to establish the chronicity and growth rate of any cysts noted.

After a clinical evaluation, the radiographic features can be incorporated and help the clinician to arrive at the most likely etiology for the cystic lesion. Based on that determination, recommendations for additional evaluation or surgical resection can be made.

- Asymptomatic patients who have a typical microcystic SCA do not need additional testing and do not need regular ongoing imaging follow-up.

- Patients with clinical and radiographic features suspicious for MCN regardless of symptoms or chronicity should be evaluated for resection without additional testing.

- Patients with main duct IPMN regardless of symptoms or chronicity should be evaluated for resection without additional testing.

- Patients with sub-centimeter pancreatic cysts who are asymptomatic and in whom the cyst has been present and without growth over 3-5 years do not need referral and can be observed either clinically or with infrequent surveillance imaging.

- Patients with symptoms thought to be the result of a pancreatic cyst should be evaluated for resection.

- Patients with pancreatic cysts with enhancing or solid component should be evaluated for resection regardless of size or other features.

- Patients with pancreatic cysts > 1 cm and of indeterminate etiology should undergo additional diagnostic testing in order to determine if the cyst is of high enough risk to warrant either routine surveillance or resection. Evaluation with endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) and dedicated MRI sequences can help the clinician to determine if the lesion is mucinous and to evaluate for “worrisome” or “high-risk” features (e.g. cysts > 3 cm in size, mural nodules, abrupt change in MPD caliber etc). This group of patients requires a thorough risk/benefit evaluation and discussion with a specialist about the evolving guidelines and data in this growing field.

FOR MORE INFORMATION

The Liver and Pancreas Center at UW Health offers a multidisciplinary approach to patient evaluation and treatment, and its surgeons perform a higher volume of complex liver and pancreas operations than any other center in Wisconsin. To refer a patient or request a consult, contact the Hepatobiliary Pancreas Clinic at (608) 263-7502.

Citations

Chandwani R. Cystic Neoplasms of the Pancreas. Annu. Rev. Med. 2016. 67(20):1-20.

Megibow et al. Management of Incidental Pancreatic Cysts: A White Paper of the ACR Incidental Findings Committee. Journal of the American College of Radiology 14 (2017): 911-920.

Scheiman et al. American Gastroenterological Association Technical Review on the Diagnosis and Management of Asymptomatic Neoplastic Pancreatic Cysts. Gastroenterology (2015): 148:824-848

Tanaka et al. International consensus guidelines 2012 for the management of IPMN and MCN of the pancreas. Pancreatology 12 (2012): 183-197.

Tanaka et al. Revisions of internationall consensus guidelines for the management of IPMN of the pancreas. Pancreatology 17 (2017): 738-753.

More information for providers

We regularly post updates about new clinical topics and techniques on our website. To get the latest information, sign up for our mailing list.