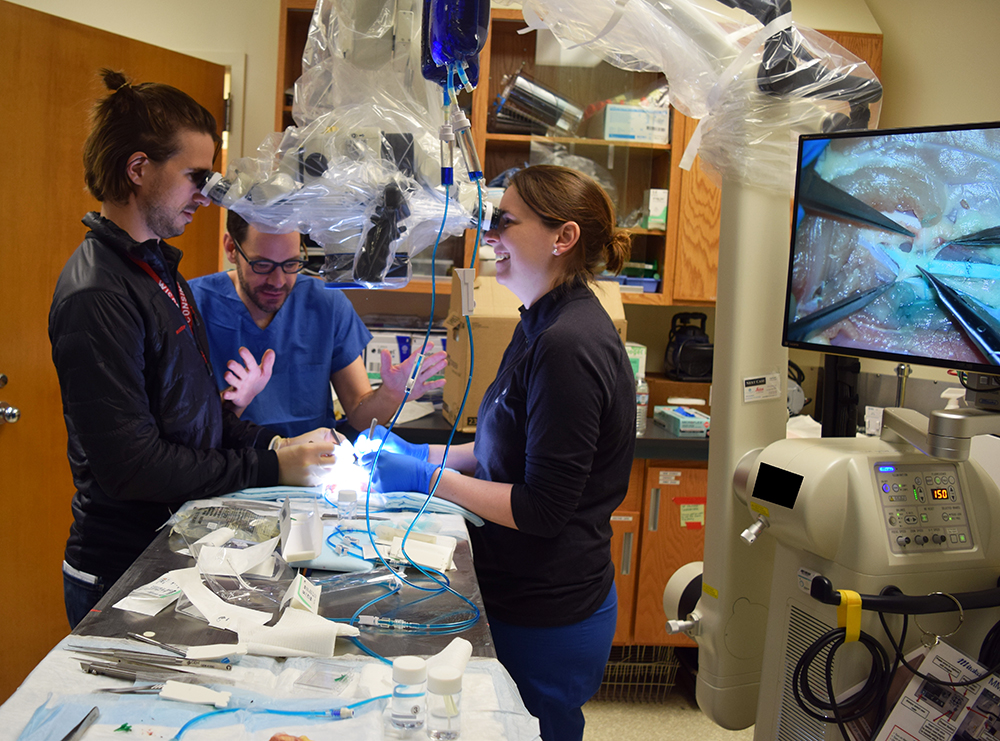

A resident practices microsurgery training on a chicken thigh in the Plastic Surgery Basic Science Lab.

The UW Department of Surgery is at the forefront of training residents in microsurgery, a surgical discipline that combines magnification, precision tools, and specialized operating techniques. Samuel Poore, MD, PhD, Weifeng Zeng, MD, and Michael Bentz, MD, of the Plastic Surgery Division have developed a comprehensive curriculum that teaches residents how to perform these techniques—making the University of Wisconsin one of the first medical schools in the nation to standardize microsurgery training.

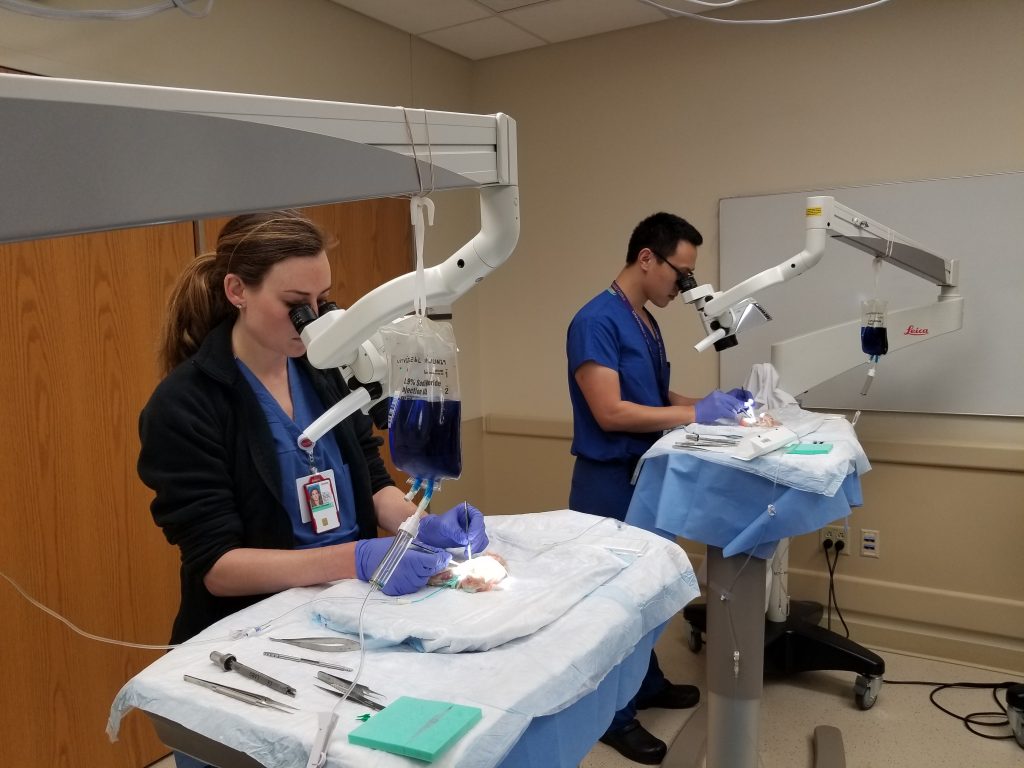

Microsurgeons connect tiny blood vessels and nerves (ranging from .5 to 3 millimeters) to allow for the transfer of tissue from one part of the body to another and to reattach amputated parts. Training outside the operating room is crucial to a resident’s success.

“The operating room is not a good place to teach how to connect blood vessels together,” says Dr. Poore. Instead, microsurgery simulations allow residents to conquer their anxiety while practicing advanced techniques.

Most of the simulation training happens in the Plastic Surgery Basic Science Lab, run by Dr. Poore. “The more training that takes place in the lab, the less stressful it is for everybody,” says Dr. Poore.

One focus of the curriculum is on the actual technical skills required to suture two blood vessels together. With that in mind, Drs. Poore and Zeng developed the “Blue-Blood” Chicken Thigh Simulator, which was published in the Plastic Reconstructive Surgery Global Open Journal in April 2018.

Chicken thighs have vascular bundles—arteries and veins—comparable to those doctors suture in the OR. Chicken thighs have been used for training previously, but the Plastic Surgery Basic Science Lab’s innovation was to perfuse the system with IV fluid dyed blue. The liquid mimics blood flow. If a suture isn’t tied properly, the blue fluid is easy to see. Every resident trains using the “Blue-Blood” Chicken Thigh Simulator and has uniformly improved their skills in a fundamental way. The lab has a flexible schedule to meet the needs of residents, who sign up via email with Dr. Zeng.

“We are a year into this,” says Dr. Poore. “We’ve seen residents go from not being able to stitch blood vessels well at all, to being able to do it perfectly. It’s really working—and it’s really fun.”

Dr. Zeng says that first-year residents come to the microsurgery training lab out of curiosity. By the fourth year, residents are gaining self-confidence in their surgical skills and they practice more. Fifth- and sixth-year students come to the lab to demonstrate what they’ve learned.

Dr. Zeng points out that residents get immediate feedback on their work. He guides residents to not make the same mistake over and over again.

“Practice makes perfect,” says Dr. Zeng. “Nobody is born to be a microsurgeon. Training is key.”

Another component of the curriculum is the once-a-year training course in microsurgery. This day-long intensive course is supported by several Divisions and Departments at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health—including Plastic Surgery, Otolaryngology, Urology, and Neurosurgery. Faculty and residents from other institutions participate as well. Past courses have featured guests from Baylor School of Medicine, Medical College of Wisconsin, the University of Iowa and the University of Minnesota.

Drs. Poore, Zeng and Bentz are now evaluating the effectiveness of this new curriculum. “To change the way we educate people, we must be innovative,” says Dr. Poore. “Innovations start outside of the OR and have to move in to the OR.”